JFK's Death Wasn't Just An End - It Was Also A Crucial Beginning

(CNN) -- President John F. Kennedy's assassination 55 years ago this week permanently transformed American politics, thrusting the nation toward a long overdue -- and still unfinished -- reckoning with our democracy's painful history of violence and racism. For a brief moment, Kennedy's death produced a kind of national unity not seen since World War II, opening up political space for the new president, Lyndon Johnson, to push through watershed civil rights and voting rights legislation in 1964 and 1965.

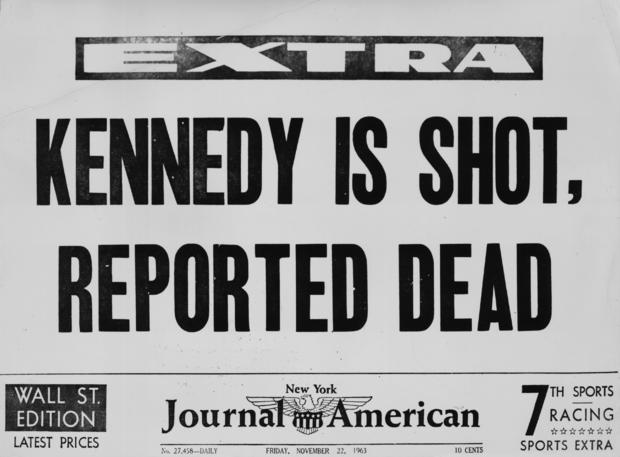

President Kennedy's death on November 22, 1963 in Dallas shocked many Americans out of the political stupor of the Eisenhower years, a time mythologized by some even today as as a sepia-toned era of economic plenty and cultural innocence. Kennedy's greatest legacy and contemporary tribute remains the fact that, during his final months as president, he embraced a liberated American future, one that is still being debated today but came one step closer to realization through the strength of his leadership.

The advent of the 1960s came at a moment when Cold War liberalism had identified the Soviet Union as America's greatest existential threat. President Kennedy's only inauguration speech bore out this logic; he famously observed that America stood prepared to "pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty."

But Kennedy's 1961 inaugural address focused on external threats just as domestic unrest stirred around racial justice and the struggle for black dignity. A televised address, almost 2½ years into his tenure, would be his finest moment as president. On June 11, 1963, against the backdrop of Alabama Gov. George Wallace's infamous threat to stand by the schoolhouse door to prevent the University of Alabama from being racially integrated, John Kennedy firmly and eloquently supported black citizenship.

Civil rights demonstrations and protests in Birmingham, Alabama, and cities across the nation inspired Kennedy to deliver the speech. The President, previously best known for his cool demeanor and piercing intellect, gave a rousing defense of racial justice that evening that characterized, following the words of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the civil rights movement as a moral imperative. "A great change is at hand, and our task, our obligation, is to make that revolution, that change, peaceful and constructive for all," Kennedy said. "Those who do nothing are inviting shame as well as violence," he warned. "Those who act boldly are recognizing right as well as reality."

Kennedy's assassination ended his burgeoning efforts on civil rights, which were buoyed by the work of millions of ordinary Americans, to create a political consensus that recognized black citizenship and racial justice as the key to the nation's future. Ironically, his sudden death at the hand of an assassin's bullet set the stage for historic legislation that would expand American democracy -- extending the franchise and civil rights of people of color -- even as it revealed new depths of division along racial, cultural and political divides.

In a sense, America came undone after the Kennedy assassination and remade itself by accepting some hard truths about its history. The roughest parts of that history could be seen in proliferating civil disorders that critics labeled riots and social justice advocates called rebellions. By decade's end the forward-looking, handsome and ambitious young president had been replaced, improbably, by the man he defeated in 1960 -- Eisenhower's vice president, Richard Nixon. Nixon won victory on a promise to turn back the clock to a more peaceful domestic era, one ruled by law and order where average Americans felt safe from the anxiety of social unrest. Nixon staked his entire presidency on the reversal of Kennedy's affirmation that racial justice could not be stopped by police power.

Nixon's rewriting of history helped to define the 1970s, the decade after Kennedy's assassination, as did the roiling social protests by blacks, women, Native Americans, Latinos, Asian-Americans, gays and lesbians, and poor people. Debates over the Vietnam War and poverty exploded into what seemed like open warfare between young baby boomers who craved a new world and an older generation, many battle-scarred by the Second World War, who prized a tenuous domestic peace over justice for groups who had been left out of Eisenhower-era America's prosperity.

Kennedy's youthful image, alongside that of first lady Jacqueline Kennedy, is a kind of Rorschach test for our time. What feelings do images of the young president and the subsequent assassination evoke? For some, it's a deep loss of innocence. For others, Kennedy represents the unfinished promise of our democratic experiment.

Looking in retrospect, we can see that Kennedy transitioned to power during an era of enormous domestic and global change, where America's hidden face of racial segregation, poverty and violence became clear for all the world to see. America's Janus-faced response found one portion of the country heeding King's call to build a "beloved community" and finding strength in the country's diversity. Another portion resisted calls for change by turning inward and embracing a past that refused to come to terms with a national history of inequality.

Fifty-five years after Kennedy's assassination, America is once again coming undone and remaking itself before our very eyes. President Donald Trump's pledge to "Make America Great Again" drew inspiration from Nixon's playbook, framing America's present as a tragic departure from a glorious past. Where President Kennedy embraced America's multiracial and multicultural makeup as offering the entire nation a better future, Trump's rhetoric remains mired in a past that, upon closer inspection, excluded millions of Americans from dreams of freedom, equality and justice. Kennedy's vision, which would be institutionalized through much of the legislation enacted under Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, reverberates through contemporary debates about the future of American democracy.

This year, commemorations of the Kennedy assassination fall on Thanksgiving. Kennedy's death is still marked as the tragic end of the bucolic postwar American dream. This is both unfortunate and shortsighted. Kennedy presided over a transformational era in American politics, a moment of national reckoning on issues of race, democracy and citizenship. Rather than viewing Kennedy's death as the end of an era, we should remember it as the start of America's Second Reconstruction, a period that would usher in new freedoms for a wide spectrum of historically marginalized citizens. Kennedy challenged Americans to brave new domestic and global frontiers without fear. On this score, he led by example and in doing so, left us with enduring hope that we could be as courageous and forward-looking in our time as he was in his.

The-CNN-Wire™ & © 2018 Cable News Network, Inc., a Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.